Project details

Project site: https://imaginingfuture.unc.edu/

April 21, 2021: Imagining the Future: Public Art Confronts the Past

I created a site-specific public art project at the Center for the Study of the American South, on view beginning in August 2020 and on display through 2021. My project intervenes throughout CSAS’ location in a historic home on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The installation encompasses sculptures that evoke the historic fire screens found in house museums from the 19th century in the United States, as well as a wallpaper display that depicts an illusory excavation into the walls of the building.

CSAS’ offices are located in a renovated building, the Love House, that is the former home of Cornelia Phillips Spencer. Spencer is a well-known figure on UNC’s campus. She was a white woman who was active as an author and historian in the mid-to-late 19th century in Chapel Hill. Her copious writings evince white supremacist and patriarchal beliefs. Her influence on the university was intertwined with her political activism that advanced Lost Cause Confederate mythology during and after the Civil War. Her impact has had a strong presence on campus in the 20th century, with a campus dorm and special award named for her. Her legacy has also been questioned on campus, most notably by students, faculty and staff in the early 21st century.

Despite the repeated calls to remove Spencer from an honorific position in campus memory, a portrait of Spencer, along with reproductions of several of her botanical watercolors, hang in the main parlor of the Love House. My project takes on the complex and troubling endowment of Cornelia Phillips Spencer, weaving together Spencer’s own words as irrefutable evidence in the persistent lineage of perpetual racism and sexism in the University’s official actions in our present day.

The title of the project takes on the profiling of Spencer as the “woman who rang the bell” at the University when classes resumed during the post-Civil War period. The title also refers to the concept of how exposure to gross inequity, in this case the reality of Spencer’s white supremacist beliefs, is cause for reconsideration and dismantling of the honorific position she has been placed into in UNC history. Spencer once wrote, “”If one or at most two or three hearts hold me, when dead, in faithful remembrance, it will be as much as I ask, or expect.” In faithful remembrance is a response to the necessity of proactively working to undo what has been done, aligning with the principles of reckoning that the Imagining UNC’s Future with Art project has centered.

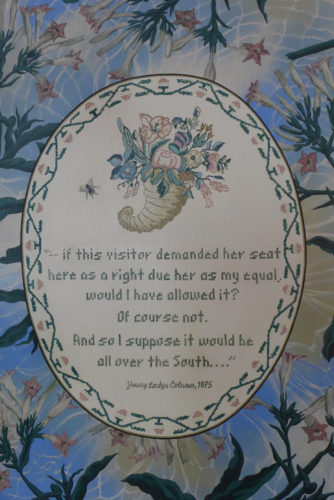

The painted sculptures are distributed throughout the Love House building, in front of the 5 fireplaces extant today. Historic fire screens were domestic objects typically made of wood or metal that assist in regulating the warmth of a parlor fire for those seated nearby. Fire screens often feature precious paintings and embroidery, often by upper middle class young white women, as a display of their technical skill and trained virtuosity. Pastoral scenes and decorative patterns were common visual themes, and the fire screens I made for ‘Imagining UNC’s Future with Art,’ recycle appropriations of Spencer’s own floral paintings (held in the Southern Historical Collection of Wilson Library at UNC) as backdrops for embroidered texts.

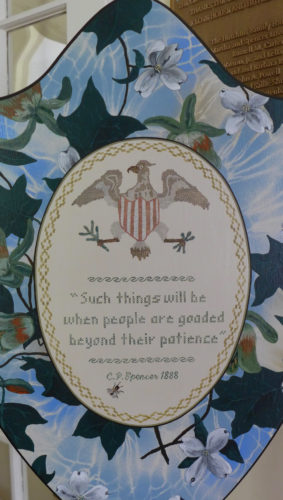

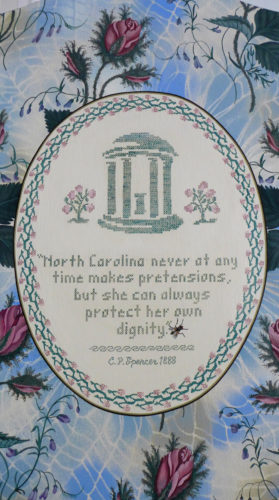

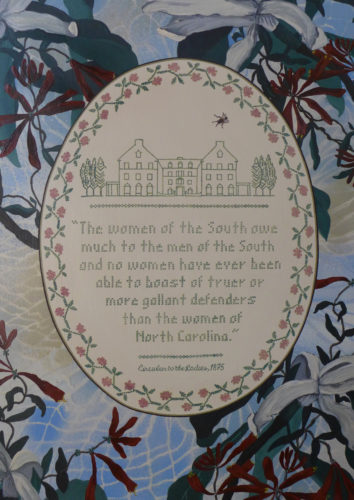

The texts, rendered to appear as embroidered embellishments, are culled from Spencer’s letters, newspaper columns, and books published during her lifetime. The five themes that the fire screens present in painted text are:

1/ Spencer’s apologistic stance on the Ku Klux Klan’s white supremacist terror (“punishing criminals whom the law had failed to punish. . . Such things will be when people are goaded beyond their patience”);

2/ Her passionate attacks on the Civil Rights Bill of 1875 and her insistence on defending white paternalism (“ — if this visitor demanded her seat here as a right due her as my equal, would I have allowed it? Of course not. And so I suppose it would be all over the South. . . .”);

3/ Spencer’s role in helping close UNC during the Reconstruction era to maintain racial segregation, then avenging to re-open the college for education to only elite white men (“North Carolina never at any time makes pretensions, but she can always protect her own dignity”);

4/ Spencer’s fundraising efforts to supply the newly reopened university with subscription monies and educational instruments, connecting this effort with the sacrifices made for women by men during the Civil War, and to the ‘pious duty’ of Confederate women laying wreathes on the graves of the ‘young heroes’ (“The women of the South owe much to the men of the South, and no women have ever been able to boast of truer or more gallant defenders than the women of North Carolina.”);

5/ Spencer’s racist revisionist history of the bi-racial coalition building during Reconstruction, which she sought to demolish (“It was an influence of the worst kind”).

Despite Spencer’s arguments for a limited role for women in public life and education, she herself found many ways as an educated middle class woman with elite political access to express herself and influence regional opinion. The genteel nature of the Love House’s domestic setting and the alacrity of the screen paintings contrast the sentiments expressed by Spencer. These fire screens bring together an historic form that would have been possible for Spencer to have decorated in her youth, given her ancestry as the daughter of a Dutch/English family in the northeastern United States, with her public expressions as a mature woman in a key period during Reconstruction in North Carolina history. For her boosterism, she has been honored on UNC campus with a dorm on Franklin Street in her name, which is also depicted in one of the fire screens.

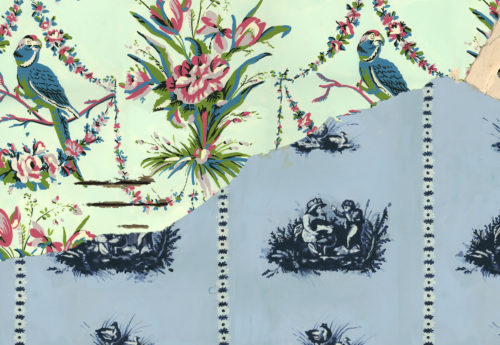

A second intervention in the Love House is in the main front parlor, installed behind the framed portrait of Spencer, and her paintings. The artwork takes on the illusion of an excavated wall, with wood lath and wallpaper fragments appearing as if uncovered beneath the present-day wall. Made of enlarged digital prints produced from hand-painted originals, the images appropriate from three historic wallpapers found at the sites of forced enslavement in North Carolina. These sites are: The Kenan family’s Liberty Hall property in Kenansville, the Rosedale property in Charlotte, and the Rose Hill property in Yanceyville. Each of these estates is not only directly tied to UNC due to a key family member’s attendance as a student, but also in a symbolic capacity as a representation of sites of power that Spencer, despite living on the margins of plantation society, called on to defend and uphold the old plantation order. The illusory excavation of the artwork emblematizes the political, social, economic and racial terms that defined Spencer’s values, rendering visible the relationship between UNC history and present-day struggles for reckoning and truthtelling.

Video documentation and interview

Additional Support:

This project has been partially supported by a Maker-Creator fellowship at the Winterthur Museum in Delaware, where I conducted research in their collection of historic fire screens, as well as with their library resources.

Tyler Brunner and Ann Walsh assisted with fabrication of the fire screen forms in Baltimore, and Color Wheel Digital printed the wallpaper.