Project details

Lauren Frances Adams mines the histories of early exploration, colonialism, and industrialization to make new and surprising connections to contemporary sociopolitical issues. Employing a variety of media from paintings and drawings to textiles and printmaking, she engages obscure imagery and phenomena to explore the relationship between labor and material culture. Purposely anachronistic, her objects and installations are also deeply relevant for suggesting how we understand power dynamics today.

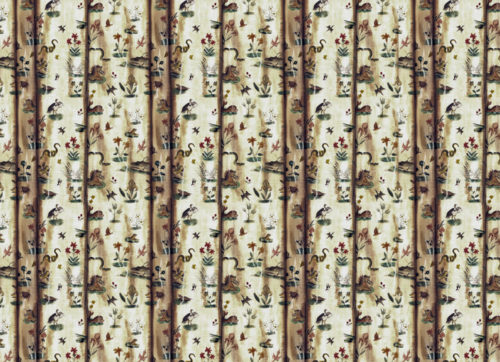

In the Front Room, Adams presents a multi-part installation that furthers her research into early encounters between the leaders of Elizabethan England and the North American “New World” in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. On the walls of the gallery, she has installed custom wallpaper titled Spectacle of Hardwick Hall (2012). Drawn by hand and reproduced digitally, the design features symbols found in the large portrait of Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) that hangs in the 16th-century Hardwick Hall estate in Derbyshire, England. In the painting (c. 1592; attributed to Nicholas Hilliard, 1547-1619), the queen wears an unusual, voluminous gown embroidered with images of flora and fauna native to the English colonies as well as imagined creatures, such as serpents and monsters. Demonstrating the breadth and depth of her power, the queen’s costume literally contains a world within it. This bringing together of the foreign with the fantastical suggests an exoticization of the colonies as a sensuous albeit perilous “other.” Adams’s translation of this imagery into a repetitive wallpaper pattern calls attention to their peculiarity while neutralizing their potency as royal propaganda.

Also featured in the installation is a large gouache painting titled The Lost Colony (2012). Whereas Spectacle of Hardwick Hall isolates a particular feature of Elizabeth’s dress as a commentary on the riches of empire, this painting conflates the aesthetics and behavior of occupier and occupied. Adams has painted an image of a dancing Algonquin Indian, which she modeled on a 16th century print by Theodor de Bry (1528-1598) that was inspired by John White’s (c. 1540-1593) watercolors of Algonquin Indians in Adams’s home state of North Carolina. The male figure wears a feather headdress and assumes an active pose, brandishing an arrow in hand. His elongated body is adorned with layers of various Elizabethan-era collars of various textures and styles. These have the effect of appearing to civilize, feminize, and also constrict the figure, literally strangling him in fashion. In effect, the painting hybridizes signifiers from both cultures, illustrating the ultimately unsustainable relationships between British and Native American peoples.

The final component of the installation is Bad Seed (2012), an arrangement of hollowed-out, painted-black gourds, interspersed with several strands of freshwater pearls on the gallery floor. Indigenous to the New World as sustenance, here the gourds assume an ornamental function in the same way that pumpkins and Indian corn have evolved from bumper crops to autumnal ornaments. Adams treats the pearls in a similarly inverse manner to producing wallpaper from the pattern of Queen Elizabeth’s gown; both gestures reduce luxurious high fashion to interior decoration. On a deeper level, the stark contrast between the black gourds and the white pearls references the charged racial and ethnic dynamics instantiated in the New World and that have persisted throughout American history.

The title of the exhibition, “Hoard,” refers to the aggregation of wealth and resources by the colonizers of the New World as well as the larger notion of creating an iconographic taxonomy of empire. Through Adams’s appropriation and transformation of colonial imagery — originally intended to denote power and grandeur — into decorative, often fabricated designs, Hoard demonstrates the deterioration of meaning that can accompany the accumulation of things — or, in the case of pre-colonial America, that of people and places as well. Adams collages these abstracted elements together, creating charged absurdities that reflect centuries of inequity. Simultaneously visually alluring and symbolically complex, the works in Hoard remind us how the legacies of the New World’s founding remain both embedded and contested in everyday life.

Curated by Kelly Shindler